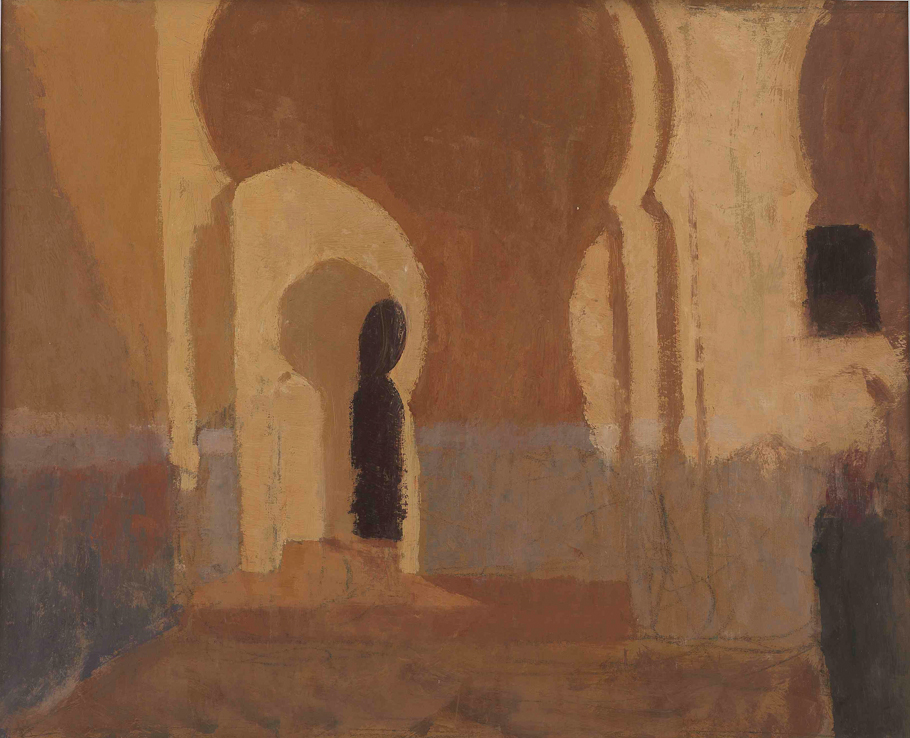

Colin Watson, Marrakech 2007

“He saw the lightning in the east and he longed for the east, but if it had flashed in the west he would have longed for the west. My desire is for the lightning and its gleam, not for the places and the earth. The east wind related to me from them a tradition banded down successively from distracted thoughts, from passion, from anguish, from my tribulation, from rapture, from my reason, from yearning, from ardour, from tears, from my eyelid, from fire, from my heart, that ‘He whom thou lovest is between thy ribs; the breaths toss him from side to side’.”

From ‘The Tarjuman al-Ashwaq’ (XIV) 1-5 by Muhyi’ddin Ibn Al-Arabi

The painter, longing for the gleams and breaths of a higher realm seeks their manifestations in a form. An outward order and balance, of an almost ceremonial aspect. In a place where the life and sounds of the street have receded, where the trysts and transactions of the daily round linger only as so many collected thoughts, imperturbable. One is made aware of how human conduct reflects this world’s construction. Here, in this peculiar light, in this luminous shadow, the eyes and heart must re-adjust.

Emotional, intellectual and spiritual yearnings are interpreted in languid poses and concise gestures. Graceful arrangements stand as monuments to fragile and passing moments, as though solemn gatherings were being marked before a great separation. These timeless processionals link past, present and future. Childhood anticipation and mature contemplation unite in a youthful unselfconsciousness, These are at once simple folk and angelic creatures, paupers and princesses. The structure of their reality seems directly linked with their values, and indeed with those of the painter himself.

Amid complex rhythms and movements one is struck by how work and leisure, stillness and activity, solemnity and joy inter-connect so naturally. A single meditative figure, a dark archway, a sparsely bedecked tree or the upright of a distant minaret. These horizontal points of contact with the vertical become spiritual axes punctuating the pictures as times of prayer punctuate the day.

It is a time when the sun’s sloping rays catch the distant hills and the warm air seems to constrain movement, giving the impression of conserved energy. A brooding presence in both “The Rooftop” and “Breaking the Fast” is that of the still figure at the extreme right of both compositions. Each seems to cast a spell over the whole scheme conveying an ambiguous mood of calm wisdom and troubled resignation while the others play out their roles almost unawares. In “The Rooftop” the robed man’s authority is evoked in the double dome of cap and window above while the dark interior, an emanation of his more solemn thoughts, is beautifully countered in the mysterious presence of the woman who turns away from us. Similarly, the stable calm of the pensive woman to the right in “Breaking the Fast” is strengthened by the triangle of her headscarf, quietly echoed in the small window just visible through the central archway. Again, the dark column rising behind suggests the seriousness of her role, reiterated by the shadowy central room beyond The slightly troubling effect of the curtain’s diagonals give the whole a subtle air of expectation. In such a way one’s enquiry is rewarded, one’s understanding enhanced by a careful search for echoes and repetitions, inversions and counterpoints throughout the works.

The smaller paintings also continue this notion of the inter-relatedness of all things. Nature extends into the man-made. We note the same glowing light, the same retreat into secluded quarters. Here too mundane activities seem perfumed by the sacred. The daily trip for provisions, the passing glance of friends and strangers, the greeting by the gate, all seem, in this moment of depiction, solemnised, as though yielding a deeper significance. And perhaps at last it is here that we apprehend the elusive divine gleam.

Mark Shields, February 2007.